For decades, heart disease has been mistakenly seen as a predominantly male issue. However, cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death for women, accounting in Canada for more than 35,000 deaths in 2022. This is seven times more than breast cancer deaths and far higher than deaths from chronic lung disease (over 6,000) and Alzheimer’s (over 3,500).

Recognizing the importance of this issue, the UBC Division of Cardiology invited leading cardiologist Dr. Martha Gulati to present at Grand Rounds on March 6, 2025. Dr. Gulati emphasized that women are not just “small men.” Women experience unique risk factors, symptoms, and outcomes that demand a tailored approach to prevention and treatment.

Delays and Worse Outcomes

Studies consistently show that women with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have a higher mortality rate than men. The ISACS-ARCHIVES study, which analyzed over 87,000 patients, found that women had a higher 30-day mortality and increased risk of acute heart failure, particularly after ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The VIRGO study highlighted that young women under 55 who experience AMI face a significantly higher risk of coronary-related and non-cardiac hospitalizations within a year of discharge.

Yet, many women do not present with the classic crushing chest pain often associated with heart attacks. Instead, they may experience shortness of breath, nausea, fatigue, or jaw pain, leading to delays in diagnosis and treatment. The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (2014–2018) revealed that women presenting with chest pain in emergency departments waited 10 minutes longer than men for initial assessment and were less likely to be admitted.

Beyond delays in care, women are less likely to receive life-saving interventions. Data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2006–2015 showed that women with STEMI and cardiogenic shock were less likely to undergo revascularization, receive mechanical circulatory support, or other invasive cardiac procedures, resulting in higher mortality rates.

Biological Differences Matter

Women also face unique biological and hormonal factors that influence cardiovascular risk. They are more likely to experience ischemia with no obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA) and Takotsubo syndrome (“broken heart syndrome”), both of which are frequently misdiagnosed. Additionally, pregnancy-related complications such as preeclampsia and gestational diabetes significantly increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease later in life.

Despite these risks, women are less likely to receive high-intensity statins, appropriate anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation, or Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) and/or Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (CRT) therapy, even though research suggests they may benefit more than men. The underuse of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and heart failure therapies further underscores the treatment gap.

Closing the Gap

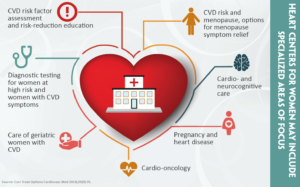

The medical community is now working to bridge these disparities. Experts like Dr. Gulati and Dr. Tara Sedlak are calling for:

• Improved awareness of sex-specific heart disease symptoms

• Equitable treatment guidelines tailored for women

• Increased representation of women in cardiovascular clinical trials

The data is clear: women are at risk, and systemic change is needed. With ongoing research, policy changes, and education, the goal is to ensure women receive the cardiovascular care they need and deserve.

References

Cenko E, et al. Sex differences in heart failure following acute coronary syndromes. JACC Adv. 2023;2(3):100294. doi:10.1016/j.jacadv.2023.100294

Bucholz EM, et al. Sex differences in cardiac risk factors, perceived risk, and health care provider discussion of risk among young patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(18):1949-1957. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.859

Jiang L, et al. Younger women vs men have worse outcomes following AMI: subanalysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(18):1753-1764. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(23)02259-0

Banco D, et al. Sex and race differences in the evaluation of young adults presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11(9):e023918. doi:10.1161/JAHA.121.023918

Ya’qoub L, et al. Racial, ethnic, and sex disparities in patients with STEMI and cardiogenic shock. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(7):653-660. doi:10.1016/j.jcin.2021.01.003